Stranger Days

Horror is everywhere. It’s in fairy tales and the evening headlines, it’s in street corner gossip, and the incontrovertible facts of history. It’s in playground ditties (Ring-a-ring a roses is a sweet little plague song), it’s on the altar bleeding for our sins . . .

—Clive Barker, A-Z of Horror

It has been, as I write this, almost exactly one year since the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic and the United States entered a lockdown. It has also been almost exactly one year since I began the introduction (“Strange Days”) to the previous volume of this series with this:

These are unsettling times. The world changed forever as I compiled this anthology, and we don’t yet know what it has changed into. . . . Why, some must be asking, would anyone want to read dark fantasy or horror while a pandemic rages, the economy (and who knows what else) topples, and people are dying and suffering?

Did I answer the question? If you weren’t perspicacious enough to read last year’s anthology (tsk!) you can still buy the book and find out. Or read that introduction here.

I’m not the only one to have had similar thoughts. A recent study’s title—“Pandemic Practice: Horror Fans and Morbidly Curious Individuals Are More Psychologically Resilient During the COVID-19 Pandemic”—sums up its results and answer to the question. The researchers found that “horror fiction may not lead you to find ways to enjoy life during a pandemic, it might help you learn how to deal with the fear and anxiety that stems from something like a pandemic.”

This may be true, and it ties into the traditional view of horror: we enjoy it because it gives us a type of closure—the bad stuff, the monsters, the evil is destroyed or at least controlled. Order or some semblance of it is restored.

Restoring order, however, is not always the aim of modern dark fiction. As Gina Wisker writes, “Horror explores the fissures that open in our everyday lives and destabilizes our complacency about norms and rules . . .” It also has a “politicized role as exposer of social and cultural deceits and discomforts . . .”

Horror can comfort and give us a feeling of control but is also challenges and discomforts, even in these challenging and uncomfortable times.

Horror, I’m sure someone has noted, is nothing if not paradoxical.

*

Before we go too much further, it’s probably best to mention (as I do almost annually) that I’m not offering a definition of dark fantasy. Or horror for that matter. You can read last year’s introduction on that point or, more directly, the very first introduction to this series from The Year’s Best Horror and Dark Fantasy: 2010—“What The Hell Do You Mean By ‘Dark Fantasy And Horror?’”—also republished here.

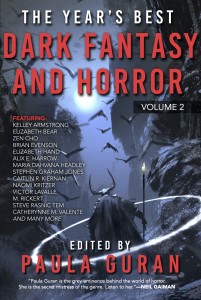

And, of course, a reminder that although this is Volume Two, it is really “volume twelve” as the series started in 2010 (covering stories first published in 2009). The title change is due to a publisher change (from Prime Books to Pyr Books).

Back to less practical matters . . .

*

During the last year, the horrific daily intruded on the mundane. But that’s the thing about horror—and dark fantasy, weird fiction, or what have you—it is rooted not only in the fantastic of nightmares and the imagination but in everyday real life.

But, given the circumstances, has my/our perception of what horror changed in the last year?

I don’t have an answer, of course. Maybe after time has passed there will eventually be one. But in the very short-term retrospective—after reading hundreds of stories, selecting thirty, and offering another two hundred as “recommended,” I have some random observations.

- It wasn’t until after I started assembling this volume that I realized how often homes, houses, and other domiciles played important roles in many of the selected stories. None of them are traditional “haunted house” tales, but the concept of “home” popped up more often than I had initially realized. Considering most of us have been home more than usual lately, this is . . . interesting.

- I often choose stories set in the future and I did so again this year—about half a dozen times. But in some cases, the futures involved seem so close, so logical, that I’m not sure they can really be considered science fiction. In a few cases, there is more of the supernatural involved in the future than science.

- Along those lines, although the stories are not all science fictional, three stories involve the human genetic code and three climate change. Again, because the stories are all wildly different, I didn’t realize this until final compilation.

- My purview for these volumes is expansive. I’ve never concentrated on “horror” per se, never really sought stories guaranteed to scare and certainly not those that merely shock. My schtick tends toward tales that disturb, unsettle, disrupt, discomfort, intrude, etc. That’s not changed, but I wonder if there was an overall trend this last year toward, well, just “dark” as opposed to “horror.” Or maybe it is just that there is a wider range of publications now featuring “dark” but not necessarily “horror” fiction.

- Along those lines, if you look at the sources of selected and recommended works—which you should and then seek them out—you’ll find a wide variety of publications. Many of them are not places one would expect to find horror or dark fantasy, yet there it is. Is darkness creeping deeper into literature or do I just find it because I am looking?

- In the last few years, genre fiction has (finally) become more diverse and more publishing opportunities have become available for writers who are not white, do not have an exclusively Western perspective, are not heterosexual, and who are not cisgender male. Consequently, the cultural milieu and characters portrayed have broadened. This positive trend has continued in the last year and, as always, is reflected in my selections. Have I chosen more of it? I don’t know, but I feel I have a great deal more to choose from.

- I didn’t realize until after biographies were assembled that about twenty of the thirty stories included are by writers who identify as women. I don’t think this the first time the contents have had a female majority, but I think that is the largest margin.

- An aspect of both the point above and what Wisker refers to as “politicized,” are the couple of blatantly feminist stories and several others with more subtle messages of that type. Again, nothing new for me or this series, but maybe (or maybe not) notable.

- Far too early for this one, but I warned you this was random. Dystopic and other science fiction often supposes governmental upheaval—although I don’t think anyone ever imagined a president of the United States denying he was defeated in a free, fair, and secure election and then urging a mob to attack Congress—but after the January 6, 2021 assault on the Capitol by Trump-supporting insurrectionists, one can’t but wonder if this will play into dark fiction now.

- Stories directly inspired by the pandemic did not, of course, start being published until later in 2020. That said, we (suitably) start volume two with a COVID-19-based tale by Victor LaValle who was commissioned (along with twenty-eight others) by the New York Times to “write new short stories inspired by the moment.” They were “inspired by Giovanni Boccaccio’s ‘The Decameron,’ written as the plague ravaged Florence” in the fourteenth century.

And that’s probably an excellent note on which to end the introducing and start with the reading.

Paula Guran

National Respect Your Cat Day 2021